As the entire world is on lockdown right now due to the global pandemic and people are “forced” to stay home, tons of daily activities that are usually outdoors or involve people gathering have moved to a virtual form over internet–teaching, working, reality TV shows, etc. Inevitably, there has also been a trend to reinvent games that would usually require social interactions and presence into an online form that can be played during social distancing. Apps such as House Party allow people to hold virtual game nights where players get to play party games such as Trivia and Heads Up together while being thousands of miles away from each other.

Zoom Video Conferencing

Zoom Video Conferencing

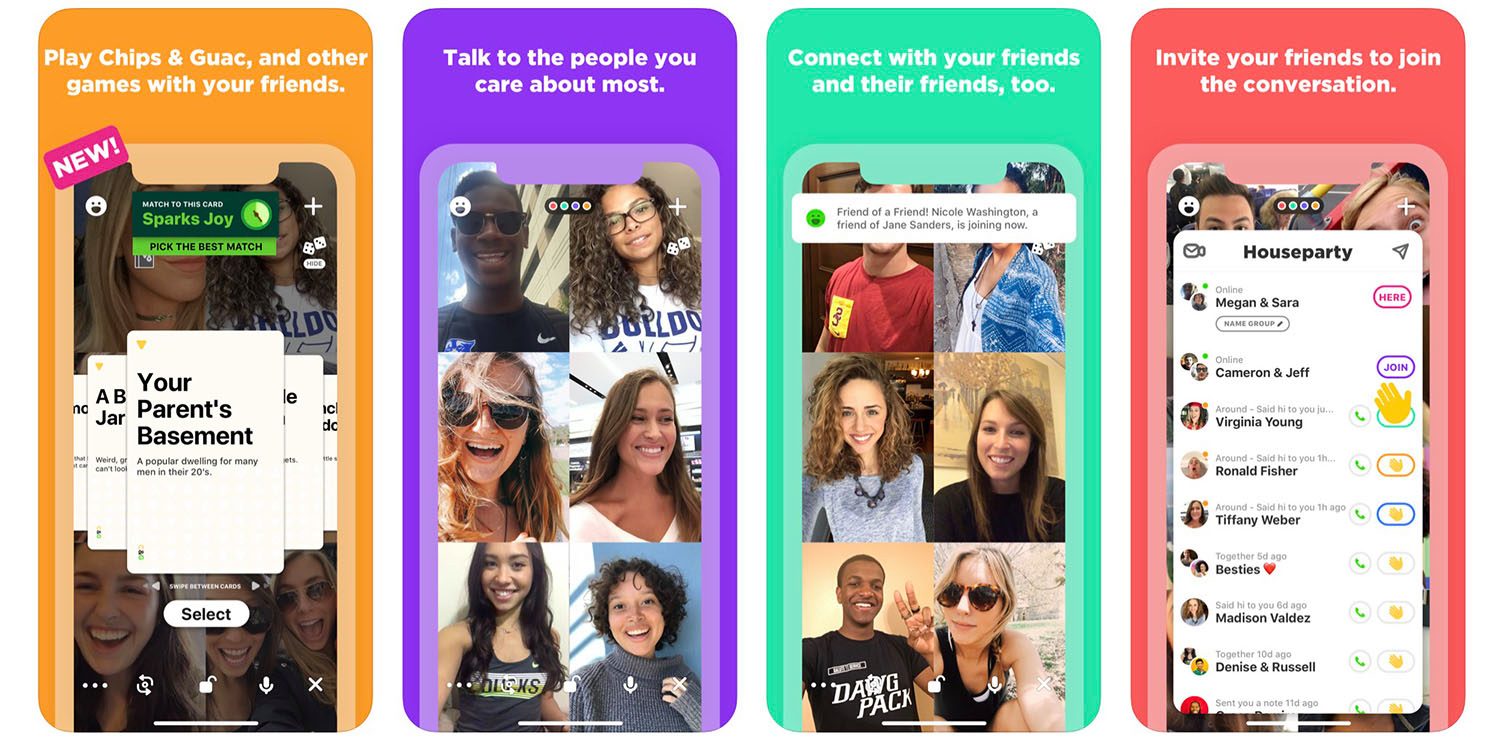

House Party

House Party

As a way to keep myself positive during this global pandemic, I thought it’d be fun to take on a challenge to design games for Zoom (or any similar video conferencing tool) during social distancing. And here are a few things I learned from the design process.

Instant Response Becomes Nearly Impossible

One of the biggest challenges to design for a video call software is to take into account of its innate lag between players in the call, since video and audio transmission takes time. What that means is that it won’t be nearly as fun to play games about speed (E.g., games about being the fastest person to do certain thing, or games involving instantly responding to another player, etc.) in a video call setting.

During an Improvisational Acting class that I’m taking right now through Zoom, we tried playing a game about free association where one player shouts out a word and the other has to instantly respond with a random word associated with that. In a face-to-face setting, the game is fun and intense since everyone would be rapid-firing words that are unexpected. If someone hesitate they lose. On Zoom however, the game became super slow because of the lag between the player giving out the word and the player responding. The game wasn’t nearly as fun because the extended wait kills the tension and the unexpectedness.

So, a lesson learned here is that a game to be played through Zoom shouldn’t be about instant reaction. There are indeed ways to still make games about speed work on Zoom. First of all, if a game is merely about who does certain things faster (E.g. spotting the difference between pictures, naming five animals, etc.), it could still work on Zoom because everyone is almost equally delayed (assuming everyone is under similar network condition). A second way to work around it is to alter the gameplay from around speed to something else. For example, the free association game I mentioned above was tailored towards telling the story behind each association later during that class as we play.

What I’ve discussed here, however, is likely to be only applicable when designing analog/hybrid games for Zoom. And certainly if you make a digital game with a decent server, you are likely not to have to worry about internet lag as much. But that’s a different story.

Monitoring Everything Becomes Difficult

Different from a face-to-face board game session or a digital game where players or a computer system can reinforce the rules and make sure no one’s cheating, on Zoom monitoring can become really difficult sometimes even with the help of the host privilege (i.e. the control over other participants you have as the host of the meeting).

When making my game Zoom Escape, which is a social game that simulates a room escaping experience, a feature I had was utilizing different sheets in a Google spreadsheet–which is something handy for Zoom games–to show different players different information. But the players are not allowed to peak into other players’ sheets or edit them. Certainly, there’s no way I can constrain where each player looks. I had to rely on trust and the “culture” of “let’s all agree that we won’t peak into other sheets”. Earlier in the design process I was also trying to limit what and when a player can communicate with others. Luckily, with the help of the host privilege on Zoom I was able to forbid private chats among players and them unmuting themselves. However, that authority kind of felt discouraging on players’ sides. And even with that, there’s no way I could tell if they were communicating with others through other means or not.

Therefore, for games to be played on Zoom, I find the most effective way to monitor is to establish a culture, an atmosphere, where players would voluntarily abide to the rules even when no one’s checking on them. And this could be done by having an engaging story setting or fantasy. In the case of Zoom Escape, the experience is about simulating being kidnapped to a dark basement, which incentivized players to stay discreet and quiet throughout the gameplay.

Inactivity Kills Player Interest Even Faster

Since players are sitting in front of a computer or their phones when participating a game session on Zoom, they can get more easily distracted by other stuff happening on their computer. Therefore, reducing inactivity and keep them engaged is even more important when designing a game for Zoom.

When making Zoom Escape, I made the choice of asking every player to private-message me their actions on their turn without letting others know what’s happening in one of my earlier iterations. I thought this mechanic would be a perfect simulation of what it feels like when players are in a dark basement and not knowing what’s going on with others, and therefore increase the engagement. However, the gameplay was boring and this design was doing the exact opposite. Players get easily distracted and started checking their phones when it’s not their turn. There were even a couple of moments where I texted a player about their turns and they didn’t realize it because they weren’t paying attention. The cause of this was that the wait for each player between their turns was way too long and unpredictable. Plus, there wasn’t anything for them to do while waiting for other players to complete their turns.

A big lesson learned here is that, though it is already dangerous to an emerging game experience, inactivity is even more dangerous for games where players are not physically together. To save a game from that, you should consider giving players purposes at all time and, most importantly, never ask them to turn off their camera or microphone.

Conclusion

Designing games for Zoom was definitely challenging, experimental, and fun. As this global pandemic goes on, this trend of moving social games and other activities online is only going to grow. And software such as Zoom or Skype might even introduce new features for more different circumstances and might even solve some of the problems I stated above. The lesson I learned here could also be potentially transferred to making games for regular medium, since the situation on Zoom is essentially a version of our real life with a few problems being magnified.